Forq Internals

This is an optional guide for fellow nerds who want to understand how Forq works under the hood. If you’re just looking to use Forq, you can skip it. The idea is to use it as the only reference needed to become Forq expert.

So, let’s go!

Stack

If you checked the Philosophy behind Forq, you won’t be surprised that I chose boring stack to build it.

The backend part is written in Go with embedded SQLite DB. Both are extremely stable, well-tested, and have great performance for the use case Forq is targeting. Further in this guide, I’ll show that a lot of Forq logic is built around SQLite features and ways of working.

I always try to rely on the standard library as much as possible, but for some things, I had to use third-party libraries. Check the go.mod for the full up-to-date list.

Since SQLite is a file-based DB, the file must be located somewhere. You can configure that via the FORQ_DB_PATH environment variable.

If you won’t set it, Forq will use the OS-specific location for that via such logic:

switch runtime.GOOS {

case common.WindowsOS:

if appData := os.Getenv("APPDATA"); appData != "" {

return toDbFilePath(appData)

}

if localAppData := os.Getenv("LOCALAPPDATA"); localAppData != "" {

return toDbFilePath(localAppData)

}

if homeDir, _ := os.UserHomeDir(); homeDir != "" {

return toDbFilePath(homeDir)

}

case common.MacOS:

if homeDir, _ := os.UserHomeDir(); homeDir != "" {

return toDbFilePath(filepath.Join(homeDir, "Library", "Application Support"))

}

case common.LinuxOS:

if xdgData := os.Getenv("XDG_DATA_HOME"); xdgData != "" {

return toDbFilePath(xdgData)

}

if homeDir, _ := os.UserHomeDir(); homeDir != "" {

return toDbFilePath(filepath.Join(homeDir, ".local", "share"))

}

}

// Return empty string instead of calling toDbFilePath("")

return ""I’d strongly recommend setting this variable explicitly in production, so you know where the DB file is located.

Another suggestion about SQLite: while choosing the platform to host Forq, prefer SSD over HDD to get better performance.

As for the UI part, I used HTMX with DaisyUI to build a simple and functional UI. Both a perfect fit for the boring tech stack. For example, I’ve learned lately that Daisy UI has zero dependencies, which is impressive, especially in the light oe the recent supply chain attacks in the NPM ecosystem.

The UI part is completely isolated from the backend. Backend exposes REST API, while the UI part has its own Hypermedia API, which is consumed by HTMX. I did it like this to be able to disable the UI part completely in production if needed. It’s not possible now, but you can simply not expose the UI port.

Once we settled on the stack, let me briefly show you the high-level architecture of Forq, so we can jump into the low-level details later.

High-level Architecture

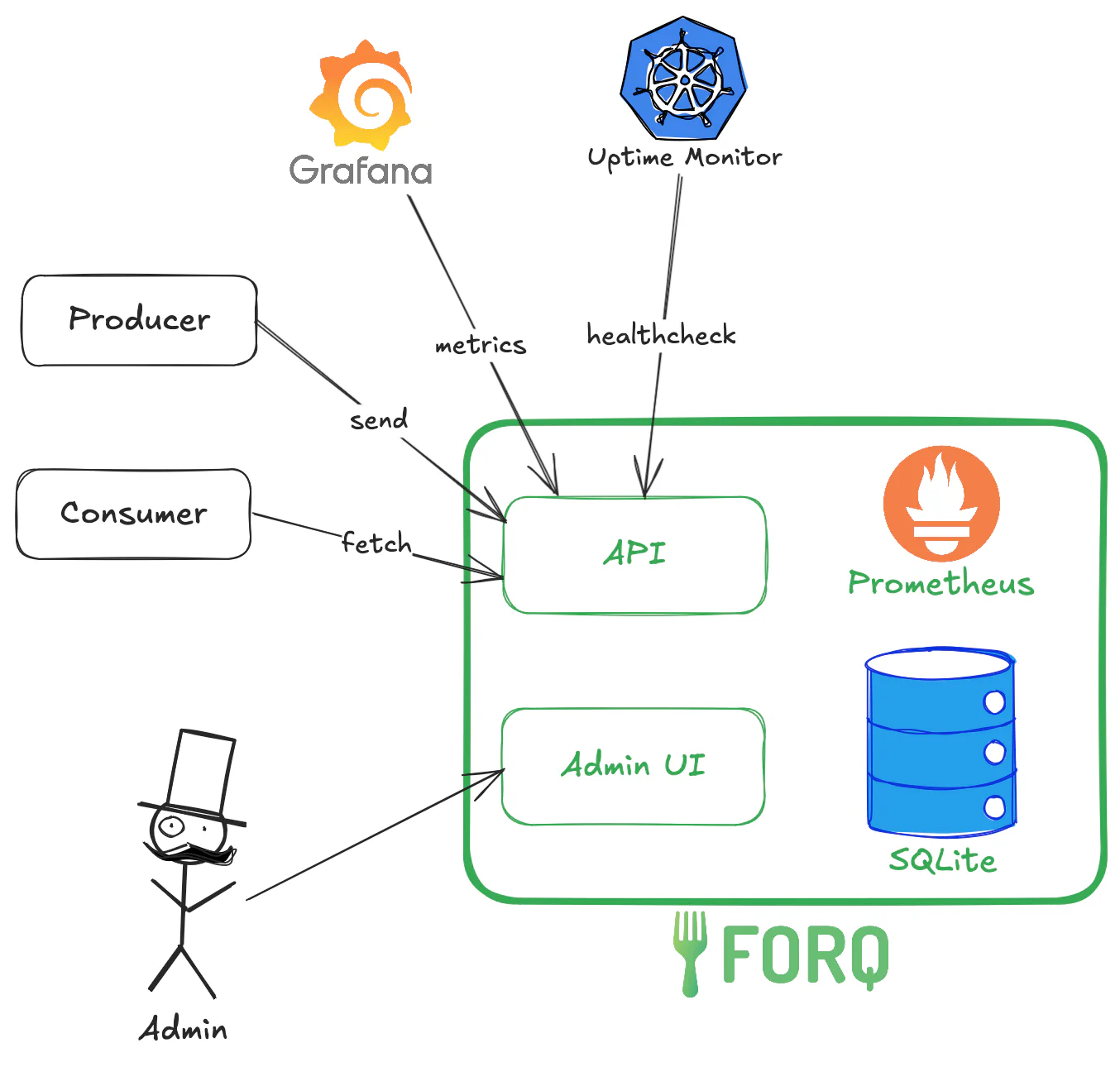

The green boxes represent the Forq service, which consists of:

- The API server, which exposes a REST API for sending and receiving messages, healtchecks, and metrics (if enabled).

- The Admin UI, which is a web interface for managing the queues and messages.

- The SQLite database, which stores the messages and queue metadata.

- (Optional) Prometheus metrics if enabled.

All of this is a single binary (or a Docker container) that you can run on your server.

The dark boxes and arrows represent the external clients that interact with Forq:

- Producers, which send messages to the queues via the API.

- Consumers, which receive messages from the queues via the API.

- Administrators, which manage the queues and messages via the Admin UI.

- Uptime monitoring service (like Uptime Kuma or Kubernetes), which pings the healthcheck endpoint to ensure that Forq is up and running.

- (Optional) Metrics server (like Grafana), which scrapes the metrics from Forq if enabled.

Now that we have a high-level understanding of Forq’s architecture, let’s dive into the low-level details.

DB design

While thinking about the structure of this guide, I thought that now we should talk about the low-level details of the consumer and producer logic. However, I realized that to understand how the producer and consumer logic works, we need to understand the DB design first.

Simply, because the DB design follow the same “simplicity” concept as the rest of Forq, so it’s a bit unconventional.

“Words are cheap, show me the code!” as Linus Torvalds says. Here you go:

-- Enable WAL mode and other optimizations

PRAGMA journal_mode = WAL; -- Multiple consumers can read messages while new messages are being inserted

CREATE TABLE messages

(

id TEXT PRIMARY KEY, -- UUID v7 format

queue TEXT NOT NULL, -- e.g., "emails" or "emails-dlq"

is_dlq BOOLEAN NOT NULL DEFAULT FALSE, -- Whether this is a DLQ message

content TEXT NOT NULL, -- 256KB max, TEXT only

status INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0, -- 0=ready, 1=processing, 2=failed

attempts INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0,

process_after INTEGER NOT NULL, -- Unix milliseconds - When the message should become visible for processing

processing_started_at INTEGER, -- Unix milliseconds - When processing started (null if not processing)

failure_reason TEXT, -- Reason for ending up in DLQ (if applicable)

received_at INTEGER NOT NULL, -- Unix milliseconds - When the message was received

updated_at INTEGER NOT NULL, -- Unix milliseconds - Last update timestamp

expires_after INTEGER NOT NULL -- Unix milliseconds - When the message expires and can be deleted

) WITHOUT ROWID;

-- WITHOUT ROWID avoids an implicit rowid column, saving space and improving performance.

-- It is safe to do that as we use UUID v7 (current timestamp-based) as primary key, and they give a good distribution in the underlying B-tree.

-- Optimized indexes for read/write heavy workload

CREATE INDEX idx_queue_ready_for_consuming ON messages (queue, status, received_at, process_after) WHERE status = 0;

CREATE INDEX idx_for_queue_depth ON messages (queue, is_dlq);

CREATE INDEX idx_expired ON messages (status, is_dlq, expires_after);

CREATE INDEX idx_for_requeueuing ON messages (queue, status);This is the entire content of the DB migration file. Let’s break it down.

WAL mode

If you are new to SQLite, you may not be familiar with the WAL mode.

Let me give you a bit of the context first: SQLite has been around since 2000. And one of the impressive facts about it is that it’s backwards compatible still today.

There is no debate that the context has changed a lot since 2000. For example, back then, most applications were single-threaded, and the idea of multiple concurrent readers and writers was not a big concern. However, today, most applications are multi-threaded, and the need for concurrent access to the database is a must. And here is where backwards compatibility shows its trade-offs: SQLite still needs to be shipped with the defaults from 2000.

Journal mode is one of those defaults. By default, SQLite uses the DELETE journal mode, which means that when a transaction is committed, the journal file is deleted. This works well for single-threaded applications, but in multi-threaded applications, it can lead to contention between readers and writers. When a writer is writing to the database, it locks the entire database, preventing any readers from reading from it. Needless to explain why it’s a problem for Forq.

WAL (Write-Ahead Logging) mode is a more modern journal mode that allows multiple readers to read from the database while a writer is writing to it. This is achieved by writing changes to a separate WAL file, which is then merged into the main database file when the transaction is committed. This allows for much better concurrency between readers and writers, making it a perfect fit for Forq.

I’d say this is on the reasonable defaults for SQLite these days if the context is multi-threaded applications.

There are other defaults that we change in SQLite for Forq. However, they are not persistent across connections, so we set them on each connection rather than in the migration file.

PRAGMA synchronous = NORMAL; -- Good balance between performance and durability

PRAGMA temp_store = MEMORY; -- Use memory for temporary storage to improve performance and reduce disk I/O

PRAGMA optimize 0x10002; -- Run automatic optimizations to improve performance on a new connection being openedTable structure

Single table

First and foremost, you might have noticed that there is a single table “to rule them all”. I know that this might offend the DB purists with decades of enterprise experience: “It is not normalized!”, “There is data duplication!”, “You should be banned from using SQL!”. Yes, I hear you. To scare you even more, foreign keys are disabled in Forq. And it’s not even Halloween yet! 🎃

Jokes aside, I think it is clear that this is just another trade-off: yes, there are some data duplication, but this gives a performance boost. No JOINs, no explicit transactions even, as I can keep all the operations atomic.

What is also means, that even though Forq is a message queue, queues are, actually, virtual rather than physical entities.

They are just represented by a string in the queue column. And you can get far with this:

- you need messages from the particular queue?

SELECT * FROM messages WHERE queue = 'queue-you-need'is your friend. - you need to see the list of existing queues?

SELECT DISTINCT queue FROM messageswill do the job. - you need to see the depth of each queue?

SELECT queue, COUNT(*) FROM messages GROUP BY queuedoes the trick.

All pure SQL, all can be optimized with indexes, and all works well for the use case Forq is targeting.

Columns

Let’s go one by one:

id

The primary key of the table. It is a UUID v7 string, and is generated by the Forq server when a message is received.

UUID v7 (unlike the v4 that is the default in many systems) is time-based rather than completely random, which means that it is sortable by time. Here is a quote from Wikipedia:

UUIDv7 begins with a 48 bit big-endian Unix Epoch timestamp with approximately millisecond granularity. The timestamp can be shifted by any time shift value. Directly after the timestamp follows the version nibble, that must have a value of 7. The variant bits have to be 10x. The remaining 74 bits are random seeded counter (optional, at least 12 bits but no longer than 42 bits) and random.

TLDR: they are great for DB primary keys, as they give a good distribution in the underlying B-tree, which improves performance.

queue

The name of the queue.

There is one thing to note here: DLQs (Dead Letter Queues) are not a separate entity in the DB.

They are just a convention: the DLQ for the queue emails is emails-dlq - see the -dlq suffix.

Nothing stops you from creating a queue with the -dlq suffix, but I wouldn’t recommend it,

as it can lead to confusion, and might expose some hidden bugs that I’m not aware of.

is_dlq

A boolean flag that indicates whether the message is in a DLQ or not.

Wait a minute, didn’t you just say that -dlq suffix is the convention for DLQs? Why do we need this column then?

Good questions! To be honest with you, this column wasn’t here at first.

Until I did some benchmarking and realized that if I need to fetch, let’s say, only DLQs, indexes are not helpful with the things like WHERE queue LIKE '%-dlq'.

Adding this simple column (which is not even a real boolean if you check the SQLite docs) is the simple, yet effective, performance optimization. And it matches with the opinionated design of Forq.

content

A content of the message as it is. It is a TEXT column, but Forq has a limit of 256 KB for the message size.

status

An integer that represents the status of the message. It can be one of the following values:

- 0: Ready - the message is in the queue and is available to be received by a consumer.

- 1: Processing - the message has been received by a consumer, but has not yet been acknowledged. The message is hidden from other consumers.

- 2: Failed - the message has exhausted all its retries.

I’m using integers instead of strings to save space and improve performance.

attempts

Forq has built-in retry mechanism for consumers. This column keeps track of how many times the message has been attempted to be processed. When a message is received by a consumer, this column is incremented by 1.

We’ll talk about this later once we get to the consumer logic.

process_after

A Unix timestamp in milliseconds that indicates when the message should become visible for processing. This is used for the optional delay message processing in Forq. If not provided by the producer, it is set to the current timestamp when the message is received.

Another use case for this field, it backoff delays for retries. When a message is unacknowledged (Nack) or becomes stale (not acknowledged within the processing timeout), this field is updated to the current timestamp plus the backoff delay.

processing_started_at

A Unix timestamp in milliseconds that indicates when the processing of the message started by the consumer. It is set to NULL when the message is in the Ready or Failed state.

This field is used to determine if a message has become stale (not acknowledged within the max processing time). We’ll talk about this later once we get to the consumer logic.

failure_reason

A string that indicates the reason why the message ended up in the DLQ. The only practical reason is for the inspection purposes in the Admin UI.

Currently, only possible values are: max_attempts_reached and message_expired.

received_at

A Unix timestamp in milliseconds that indicates when the message was received by the Forq server. It is set by Forq when the message is received.

updated_at

A Unix timestamp in milliseconds that indicates when the message was last updated.

“Updated” means one of the following:

- the message is sent for consumption

- the message is nacknowledged

- the message becomes stale

- the message is expired

- the message is moved to the DLQ

- the message is requeued from the DLQ to the standard queue

It is set by Forq whenever the message is updated. Might be handy for the inspection purposes in the Admin UI.

expires_after

A Unix timestamp in milliseconds that indicates when the message expires based on configured TTL for Standard Queues and DLQs. It is set by Forq when the message is received.

WITHOUT ROWID

By default, SQLite tables have an implicit rowid column, which is a 64-bit signed integer that uniquely identifies each row in the table.

It is a éminence grise that serves as the primary key even if you have an explicit primary key.

It exists to ensure that the underlying B-tree structure of the table is always balanced and efficient for lookups. This becomes quite handy if the actual primary key is random, like UUID v4.

It’s not the case for Forq, as we use UUID v7, which is time-based and gives a good distribution in the underlying B-tree.

Therefore, we can safely disable the implicit rowid column by using the WITHOUT ROWID clause in the table definition.

My local benchmarking shows a tiny performance improvement, but the main benefit is the reduced storage space.

Indexes

I spent a lot of back-and-forth time thinking and playing with EXPLAIN QUERY PLAN to come up with the optimal set of indexes for the use case Forq is targeting.

The queries backing the Forq API are prioritized over the ones behind the Admin UI, as the API is the main part of Forq.

Therefore, some “read” queries in the Admin UI might not be as fast as they could be, but it’s a trade-off I’m willing to make.

It’s pointless to review indexes without seeing the queries, so we’ll be getting back to them later.

SQLite gotchas

One last bit of theory before we jump into the producer and consumer logic. There some important SQLite gotchas that make it possible to do certain things in Forq that wouldn’t have worked in other DBs like Postgres or MySQL.

Single writer only

SQLite uses serialized transaction isolation level, which means that only one write transaction can be active at any given time. And you can’t change it. Even more, unlike Postgres, this locks the entire DB for writing, not just the rows being written to. For curious minds, here is the SQLite docs about locking.

This limit is the main bottleneck for Forq throughput, and due to that there is a theoretical maximum that one can squeeze out of Forq. The exact numbers are hard to say, as they are very OS and hardware dependent, as well as the workload pattern: number of producers and consumers, message size, etc.

On the other hand, this limit enables something that would be harder to implement in other DBs: it’s very easy to guarantee the order of the messages, as it’s possible to lock the DB while fetching the next message for processing. More on that later.

In general, this is a well-known limitation of SQLite, and “SQLITE_BUSY” is a common error that you might encounter when using SQLite in a multithreaded application. There are ways to mitigate this. Let’s focus on these two:

- increasing the busy timeout via

PRAGMA busy_timeout = <milliseconds>;- this tells SQLite to wait for the specified time before returning a “SQLITE_BUSY” error. The default is 0, which means that SQLite will return the error immediately if the DB is locked. - limiting the number of writer connections to 1 - this is the most effective way to mitigate the “SQLITE_BUSY” errors, as it ensures that there is only one writer connection at any given time.

After considerations, benchmarking, and consulting with Reddit SQLite community, I decided to go with the second approach in Forq. I find this approach more reliable, as timeouts are always a bit of a gamble, and I’d rather not go there.

What that means in practice is that I have 2 separate connection pools in Forq:

- a pool for read-only connections, which is for read-only operations with

(2 * number of CPU cores) + 1connections - a pool for read-write connections, which is for write operations with 1 connection only

Here is the relevant code snippet:

// Create read connection with multiple connections for concurrent reads

dbRead, err := sql.Open("sqlite", applyConnectionSettings(dbPath, false))

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

dbRead.SetMaxOpenConns(runtime.NumCPU()*2 + 1)

dbRead.SetMaxIdleConns(runtime.NumCPU()*2 + 1)

dbRead.SetConnMaxLifetime(0)

if err := dbRead.Ping(); err != nil {

dbRead.Close()

return nil, fmt.Errorf("ping read database: %w", err)

}

// Create write connection with single connection to serialize writes

// we are running optimizations pragma ONLY on the write connection, as it might lock the database for a while

// and our read flow doesn't expect any locks.

dbWrite, err := sql.Open("sqlite", applyConnectionSettings(dbPath, true))

if err != nil {

dbRead.Close()

return nil, err

}

dbWrite.SetMaxOpenConns(1)

dbWrite.SetMaxIdleConns(1)

dbWrite.SetConnMaxLifetime(0)When the DB operation is read-only, it uses the dbRead connection pool, and when it’s a write operation, it uses the dbWrite connection pool.

If you are coming from the Postgres or MySQL world (btw, I am too, and I love Postgres), that might sound a bit wierd to have 1 connection for writes only. That might be extremely slow! However, due to the nature of SQLite, it’s not that bad as it sounds.

Remember, that SQLite is a file-based DB, so the overhead of opening and closing connections is much lower than in Postgres or MySQL, as there is no network roundtrip involved. Therefore, writes are extremely fast, so there shouldn’t be any queues of operations waiting for the write connection. For example, in my local benchmarking, I was able to achieve around 1200-2500 messages per second on my old MacBook Pro 2019 depending on the scenario. That’s more than enough for the use case Forq is targeting.

API

Now that we have a good understanding of the DB design and SQLite gotchas, let’s dive into the API and how it works under the hood. Check API Reference for the full list of API endpoints.

Authentication

All API endpoints are protected by the API key authentication that should be provided in the X-API-Key header.

The API key is compared with the FORQ_AUTH_SECRET environment variable, and if they don’t match, the API returns a 401 Unauthorized response.

If you checked Getting Started, you know that if FORQ_AUTH_SECRET is not set, the API will not start.

That’s the only mandatory environment variable in Forq.

Check Configurations Guide for the full list of environment variables.

Error codes

API returns standard HTTP error codes, and in case of errors, the response body contains a JSON object with the following structure:

{

"code": "error_code"

}There is a list of all the possible error codes:

const (

ErrCodeBadRequestContentExceedsLimit = "bad_request.body.content.exceeds_limit"

ErrCodeBadRequestProcessAfterInPast = "bad_request.body.processAfter.in_past"

ErrCodeBadRequestProcessAfterTooFar = "bad_request.body.processAfter.too_far"

ErrCodeBadRequestInvalidBody = "bad_request.body.invalid"

ErrCodeBadRequestDlqOnlyOp = "bad_request.dlq_only_operation"

ErrCodeUnauthorized = "unauthorized"

ErrCodeNotFoundMessage = "not_found.message"

ErrCodeServiceUnhealthy = "forq.unhealthy"

ErrCodeInternal = "internal"

)Feel free to rely on them while implementing error handling in your clients.

The up-to-date list of error codes is always available in the API Reference.

Producer API

Let’s start with the simpler part: the producer logic.

API exposes a single endpoint for sending messages to the queue: POST /api/v1/queues/{queue}/messages that expects the following JSON payload:

{

"content": "I am going on an adventure!",

"processAfter": 1672531199000

}The content filed is required, and must not exceed 256 KB in size.

The processAfter field is optional, and if not provided, the message will be available for processing immediately.

Process after can be set to up to 366 days in the future, and must not be in the past.

Be careful with abusing the processAfter field, as the more delayed messages you have, the more disk memory Forq will use.

No good advice here, just be mindful of that, and allocate more disk space if your workload requires a lot of delayed messages,

like social media posts scheduling, or email campaigns, or privacy requests processing, etc.

The API handler processes the message in the synchronous manner, which means that it will wait until the message is persisted to the DB before returning a response to the client.

Once its persisted, the API will return a 204 No Content response, indicating that the message was successfully sent to the queue.

As you already know, queues are virtual entities in Forq, so Forq doesn’t care whether the queue exists or not, as for DB it is just a string in the queue column.

While powerful, this also comes with a caveat that Forq won’t catch if you make a typo in the queue name, and will happily “create” a new queue for you.

Forq is very welcoming, as you can see =)

The producer logic is quite simple and straightforward: it validates the input, generates a UUID v7 for the message ID, sets the timestamps, and inserts the message into the DB.

Check the messages.go file in the services package for the full implementation.

Please, note that producer logic always assumes that the message is being sent to the standard queue, not to the DLQ. Therefore, the is_dlq field is always set to FALSE when inserting the message.

Please, don’t try to send messages to {queue}-dlq queue, as it’s not the intended use case. I guess it’s a safe ask to avoid using -dlq suffix for your standard queues.

Some might say that there is a way to make it even faster by using the asynchronous processing, where the API would just accept the message, place it into the channel, and return a response to the client, while the actual DB insertion would be done in the background. And I agree with that. I’d go this way if I decided to prioritize throughput over consistency guarantees.

If smth goes wrong, like unexpected SIGKILL signal or power outage, the messages in the channel would be lost.

I don’t think that’s smth that you’d expect from a message queue, so I decided to go with the synchronous processing.

Targeting small to medium workloads makes such decisions easy to make, as there is no need to squeeze every last bit of performance.

Other than that, there is not much to say about the producer logic. It’s simple, yet effective.

Consumer API

Here is where things are getting interesting. The consumer logic is more complex than the producer logic, as it has to deal with more scenarios. Let’s discuss things step by step.

Polling for messages

The consumer API exposes a single endpoint for receiving messages from the queue: GET /api/v1/queues/{queue}/messages.

The returned message (if exists) has the following JSON structure:

{

"id": "0199164b-4dea-78d9-9b4c-c699d5037962",

"content": "I am going on an adventure!"

}Only the necessary fields are returned to the consumer. The rest of the fields are for internal use only.

If you have dealt with MQs before as a consumer, you know that consumers need to poll the messages (unless the push model is used) constantly to get the new messages. There are several ways to do that, and for Forq, I was looking for the right balance between simplicity, performance, and reliability.

I quickly discarded the idea of using WebSockets or Server-Sent Events, as they would add unnecessary complexity to the client and server. I’d need to persist the connections, handle reconnections, etc. Not fun!

A regular HTTP it is then. I could do it as simple as making the consumers call the endpoint, and if there are no messages, return a 204 No Content response right away.

This covers the simplicity and reliability, but not the performance, as the consumers would need to poll the endpoint constantly, even if there are no messages.

Both server and client would be busy doing nothing, just to check if there are new messages.

Therefore, I decided to go with the long polling approach, where the consumer makes a request to the endpoint, and if there are no messages,

the server holds the request open for a certain amount of time (30 seconds), waiting for new messages to arrive.

If a new message arrives within that time, the server returns it to the consumer, otherwise, it returns a 204 No Content response after the timeout.

Make sure your HTTP clients are configured to respect this 30 seconds timeout, as some clients have shorter defaults.

This should reduce the number of requests made by the consumers, as they won’t need to poll the endpoint constantly. It becomes even more important for the small projects, where the number of messages can be extremely low, like a few per day.

The waiting for the messages part is a simple ticker that checks the DB for new messages every 500 ms, which is not the most elegant solution, but it works well for the use case Forq is targeting.

Here the code snippet from the messages.go file in the services package that shows how it works:

start := time.Now()

ticker := time.NewTicker(500 * time.Millisecond)

defer ticker.Stop()

for {

message, err := ms.forqRepo.SelectMessageForConsuming(queueName, ctx)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if message != nil {

ms.metricsService.IncMessagesConsumedTotalBy(1, queueName)

return &common.MessageResponse{

Id: message.Id,

Content: message.Content,}, nil

}

// no message found, check if we should keep polling. Return nil if polling duration exceeded

if time.Since(start).Milliseconds() > ms.appConfigs.PollingDurationMs {

return nil, nil

}

select {

case <-ticker.C:

// continue polling case <-ctx.Done():

// client disconnected, stop polling and return

log.Error().Err(ctx.Err()).Msg("context cancelled while fetching message")

return nil, common.ErrInternal

}

}If 500 ms sounds like a lot, remember the 1 single writer limitation of SQLite. Wait a minute, why do we need writer to fetch the messages? Good question, we’ll get to very soon.

If you have a high number of consumers, you might benefit from using HTTP2, as it allows multiplexing multiple requests over a single connection. Forq server supports it unencrypted HTTP2 out of the box, so if you are running Forq behind a reverse proxy like Nginx or Caddy, you can enable HTTP2 there. I might consider adding a HTTP2 with TLS support, but that will be an opt-in, as then the user must provide the TLS certs, and I don’t want to deal with that complexity by default. I assume that Forq will be always run behind a reverse proxy in production, so H2C is enough for now. Let me know in the GitHub discussions if that’s a bottleneck for you.

Since HTTP2 is a very new protocol /s and not 100% adopted by all clients, Forq server supports HTTP1.1 as well, so you can use it with any HTTP client.

Fetching the next message for processing

We discussed that Forq relies on long-polling to fetch the next message for processing. Let’s see how we actually fetch the message from the DB.

Unfortunately, it is not as simple as making a SELECT query with LIMIT 1, as we need to ensure that the message is locked for processing by the consumer,

and is not visible to other consumers until it is acknowledged or becomes stale. Also, we must ensure that the same message is not fetched by multiple consumers at the same time.

Sounds like we need some ordering and locking, right?

After some thinking, I realized consuming the message is not, actually, purely read operation,

as we need to update the message status to processing, set the processing_started_at timestamp, and increment the attempts counter.

It’s a read-modify-write operation, which means that we need to either use a write transaction to ensure atomicity, or make this operation atomically in a single SQL statement.

I went with the latter.

Here is the code snippet from the SelectMessageForConsuming method in the forq_repo.go file in the repository package:

nowMs := time.Now().UnixMilli()

// we are ignoring expires_after here for performance boost reasons, as expired messaged are cleanup by the jobs.

// This query uses COVERING INDEX via `idx_queue_ready_for_consuming`, so it is very fast.

query := `

UPDATE messages

SET

status = ?,

attempts = attempts + 1,

processing_started_at = ?,

updated_at = ?

WHERE id = (

SELECT id

FROM messages

WHERE queue = ?

AND status = ?

AND process_after <= ?

ORDER BY received_at ASC

LIMIT 1

)

RETURNING id, content;`

var msg MessageForConsuming

err := fr.dbWrite.QueryRowContext(ctx, query,

common.ProcessingStatus, // SET status = ?

nowMs, // processing_started_at = ?

nowMs, // updated_at = ?

queueName, // WHERE queue = ?

common.ReadyStatus, // AND status = ?

nowMs, // AND process_after <= ?

).Scan(&msg.Id, &msg.Content)As you can see, we are using a single UPDATE ... WHERE id = (SELECT ...) RETURNING ... statement to fetch the next message for processing.

What happens here is:

- we are selecting the oldest message from the queue in the

readystate that is not delayed (i.e.,process_afteris in the past) - if found, we are updating its status to

processing, setting theprocessing_started_attimestamp, and incrementing theattemptscounter - the

RETURNINGclause returns theidandcontentof the updated message

We use dbWrite connection pool here, as we are performing a write operation, so data race is not possible, even if multiple consumers are trying to fetch messages from the same queue concurrently.

I spent some time tuning the performance of this query, as it is the most critical part of the consumer logic.

I believe I squeezed the most out of via the idx_queue_ready_for_consuming index.

Here is the index definition again for reference:

CREATE INDEX idx_queue_ready_for_consuming ON messages (queue, status, received_at, process_after) WHERE status = 0;process_after is the last column in the index due to SQLite nature, when you can perform range scans only on the rightmost column of the index.

Thanks to this index, the SELECT subquery is extremely fast, as it uses the covering index, and doesn’t need to access the actual table rows.

Covering indexes are a great feature of SQLite that not many people know about. It means that the index contains all the columns needed for the query,

so SQLite doesn’t need to navigate to the actual table rows.

In this case, the index contains queue, status, received_at, and process_after + it always contains the id in our DB (since we disabled rowid).

We are selecting id only, so the index is enough to satisfy the query. Pretty neat, huh?

Since subquery is fast, the overall UPDATE is fast as well, as it doesn’t do anything extraordinary rather than updating a single row by its primary key.

Did you see the comment above the query?

we are ignoring expires_after here for performance boost reasons, as expired messaged are cleanup by the jobs.It is theoretically possible that the SELECT subquery returns an expired message, as we don’t check for expires_after here.

It’s yet another trade-off: checking for expires_after would break the index (remember the rightmost rangle scan rule), and would make the query slower.

On the other hand, expired messages are cleaned up by the background jobs, so they won’t stay for too long in the DB, so it’s a reasonable compromise.

That’s how we fetch the next message for processing in Forq, and support FIFO ordering of messages in the queue for the consumers.

Once consumer receives the message for processing, it must acknowledge it (Ack) or nacknowledge it (Nack) within the max processing time (5 minutes). Otherwise, the message becomes stale. Let’s discuss these scenarios next.

Acknowledging the message (Ack)

The consumer API exposes a single endpoint for acknowledging the message: POST /api/v1/queues/{queue}/messages/{messageId}/ack. No request body is needed.

The underlying logic is quite simple: Forq tries to permanently delete the message from the DB by its ID and queue name.

Regardless of whether the message exists or not, Forq returns a 204 No Content response to the client.

Idempotency by design.

Here is the code snippet for the DB query:

query := `

DELETE FROM messages

WHERE id = ? AND queue = ? AND status = ?;`

result, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

messageId, // WHERE id = ?

queueName, // AND queue = ?

common.ProcessingStatus, // AND status = ?

)WHERE id = ? uses primary key lookup, so it’s extremely fast.

The queue = ? part is just an additional safety check to ensure that the consumer is acknowledging the message from the correct queue.

Same for status = ?, which ensures that the message is in the processing state, and not in the ready or failed state. The latter can theoretically happen if the message becomes stale while being processed.

This doesn’t drain performance, as the primary key lookup is already fast enough, and SQLite knows that there can be at most 1 row matching the id, so it doesn’t need to scan the entire table.

It is critically important to acknowledge the message after its being processed successfully, as otherwise, the message might be reprocessed by another consumer. Duplicates are bad, mkay?

Due to this possible scenario (or acknowledging after the max processing time), Forq guarantees only “at-least-once” delivery, not “exactly-once”.

Nacknowledging the message (Nack)

The consumer API exposes a single endpoint for nacknowledging the message: POST /api/v1/queues/{queue}/messages/{messageId}/nack. No request body is needed.

This endpoint should be used by the consumer when it fails to process the message, and wants to requeue it for later processing. Failures can happen due to many reasons, like temporary network issues, external service being down, etc., and being able to requeue the message is one of the pros of MQs over the request-response synchronous communication.

Let me show you the code snippet for the DB query first:

nowMs := time.Now().UnixMilli()

query := fmt.Sprintf(`

UPDATE messages

SET

status = CASE

WHEN attempts >= ? THEN ? -- failed if no more attempts left

ELSE ? -- ready if there are attempts left

END,

process_after = CASE

%s

END,

processing_started_at = NULL,

updated_at = ?

WHERE id = ? AND queue = ? AND status = ?;`, fr.processAfterCases(nowMs))

result, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

fr.appConfigs.MaxDeliveryAttempts, // WHEN attempts = ? (status check)

common.FailedStatus, // THEN ? -- failed if no more attempts left

common.ReadyStatus, // ELSE ? -- ready if there are attempts left

nowMs, // updated_at = ?

messageId, // WHERE id = ?

queueName, // AND queue = ?

common.ProcessingStatus, // AND status = ?

)where fr.processAfterCases(nowMs) is:

func (fr *ForqRepo) processAfterCases(nowMs int64) string {

var processAfterCases strings.Builder

// builds WHEN clauses for each backoff delay

for i, delay := range fr.appConfigs.BackoffDelaysMs {

if i < len(fr.appConfigs.BackoffDelaysMs)-1 {

processAfterCases.WriteString(fmt.Sprintf("WHEN attempts + 1 = %d THEN %d ", i+1, nowMs+delay))

} else {

processAfterCases.WriteString(fmt.Sprintf("ELSE %d ", nowMs+delay))

}

}

return processAfterCases.String()

}The resulting SQL query looks like this:

UPDATE messages

SET

status = CASE

WHEN attempts >= 5 THEN 2 -- failed if no more attempts left

ELSE 0 -- ready if there are attempts left

END,

process_after = CASE

WHEN attempts + 1 = 1 THEN $now + 1000

WHEN attempts + 1 = 2 THEN $now + 5000

WHEN attempts + 1 = 3 THEN $now + 15000

WHEN attempts + 1 = 4 THEN $now + 30000

ELSE $now + 60000

END,

processing_started_at = NULL,

updated_at = $now

WHERE id = '0199164b-4dea-78d9-9b4c-c699d5037962' AND queue = 'emails' AND status = 1; -- 1 is Processing$now is just a placeholder for the current timestamp in milliseconds, as I don’t know how else to show it here.

Obviously, id, queue, and status are random values for the sake of the example.

As you can see, the query is a bit more complex than the Ack query, as we need to handle several scenarios here:

- if the message has exhausted all its delivery attempts, we set its status to

failed - if the message still has delivery attempts left, we set its status back to

ready, so it can be picked up by another consumer later - we set the

process_aftertimestamp to the current timestamp plus the backoff delay based on the number of attempts - we set the

processing_started_attimestamp toNULL, as the message is no longer being processed - we set the

updated_attimestamp to the current timestamp

Forq retries the message 5 times with the following backoff delays: 1s, 5s, 15s, 30s, and 60s. You can’t override this.

Exhausting all the attempts makes the message failed. Later, it will be picked up by one of the jobs:

- if the current queue is a standard queue, the message will be moved to the DLQ

- if the current queue is a DLQ, the message will be permanently deleted from the DB

As I mentioned before, for Forq DLQs are just a convention, so Forq doesn’t care whether the queue exists or not, as for DB it is just a string in the queue column.

So, nothing stops the consumer from fetching DLQ messages. And it’s a valid use case, if you have a separate automated flow for dealing with DLQ messages.

Dealing with failed messages is outsourced to the jobs that run in the background, so the consumer logic is not burdened with this complexity. Imagine the query if we’d also need to move the message to the DLQ in the Nack flow. Yikes! I’ll cover the jobs later after the stale messages part.

Stale messages

If the consumer fails to acknowledge or nacknowledge the message within the max processing time (5 minutes), the message becomes stale.

There is no explicit stale status in Forq, as it’s rather a combination of 2 conditions:

- the message is in the

processingstate - the

processing_started_attimestamp is older than the current timestamp minus the max processing time (5 minutes)

Forq contains StaleMessagesCleanupJob to take care of stale messages. It runs every 3 minutes.

Here is the code snippet for the DB query:

query := `

UPDATE messages

SET

status = CASE

WHEN attempts >= ? THEN ? -- failed if no more attempts left

ELSE ? -- ready if there are attempts left

END,

process_after = ?, -- immediate retry for stale messages (consumer likely crashed)

processing_started_at = NULL,

updated_at = ?

WHERE status = ? AND processing_started_at < ?;`

res, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

fr.appConfigs.MaxDeliveryAttempts, // WHEN attempts >= ? (status check)

common.FailedStatus, // THEN ? -- failed if no more attempts left

common.ReadyStatus, // ELSE ? -- ready if there are attempts left

nowMs, // process_after = ? -- immediate retry

nowMs, // updated_at = ?

common.ProcessingStatus, // WHERE status = ?

nowMs-fr.appConfigs.MaxProcessingTimeMs, // AND processing_started_at < ?;

)As you can see, the query is similar to the Nack query, with main difference being that we set the process_after timestamp to the current timestamp,

so the message becomes available for processing immediately.

This is due to the fact that if the message becomes stale, it means that more than 5 minutes have passed since it was fetched by the consumer, so no need to wait any longer with the backoff delays.

I acknowledge that there is a possibility that some consumers might need more than 5 minutes to process the message, and they are not actually stale.

Being opinionated means that I need to draw the line somewhere, and 5 minutes is a reasonable default for the use case Forq is targeting.

It’s not possible to override this value, as it would mean that StaleMessagesCleanupJob intervals would need to be adjusted as well, and that would add unnecessary complexity.

Sorry if that doesn’t fit you use case. You can always implement idempotent consumers to deal with possible duplicates. But in general, I believe that 5 minutes is enough for 99.99% of use cases.

Actually, that covers the consumer logic. Congrats, you are a Forq producer and consumer expert now!

Let’s cover a few more things before wrapping up. Since we are still in the API section, let me briefly mention the Healthcheck and Metrics endpoints.

Healthcheck API

The API exposes a single endpoint for healthcheck: GET /healthcheck.

Unlike other endpoints, it doesn’t have the /api/v1 prefix.

It is purposefully done this way, so you can easily expose the API while keeping the healthcheck endpoint closed off from the public internet.

The healthcheck endpoint performs a simple ping to the DB to ensure that the DB is reachable, and returns a 204 No Content response if everything is fine.

Use a reasonable interval for the healthcheck depending on your monitoring system, as it does a real DB operation.

Metrics API

The API exposes a single endpoint for metrics: GET /metrics if you have enabled the Prometheus metrics via FORQ_METRICS_ENABLED environment variable.

I won’t go into much details here, as there is not much to share. Check the Metrics Guide for the full list of metrics exposed by Forq. That guide explains the trade-offs I made while implementing the metrics, as well as how to use them effectively. Give it a read if you plan to enable the metrics.

Alright, this covers the API section. Let’s move to the background jobs.

Background jobs

If you take a peek into the jobs folder, you’ll find 3 subfolders there:

- cleanup

- maintenance

- metrics

This a logical separation of jobs based on their purpose. Let’s discuss them one by one.

Btw, you might notice that jobs run with strange intervals: 3 minutes, 5 minutes, 6 minutes, 1 hour, 62 minutes, 89 minutes, etc.

This is purposefully done to avoid running multiple jobs at the same time, as they all use the dbWrite connection pool, and we have only 1 connection there.

So, they might eventually meet sometimes, but seldomly, not systematically.

All the jobs have the same internal structure and are running in their own goroutines during the Forq server lifetime.

They all have a ticker that runs the job logic at the configured interval, and they all have a done channel that is closed when the Forq server is shutting down,

so the jobs can stop gracefully.

Cleanup jobs

ExpiredMessagesCleanupJob

Remember we have an expires_after timestamp in the messages table that indicates when the message expires based on configured TTL for Standard Queues and DLQs?

This job takes care of moving expired messages from the standard queues to the DLQs. There is another job that deals with expired messages in the DLQs, but we’ll get to that later. It runs every 5 minutes.

Here is the code snippet for the DB query:

query := `

UPDATE messages

SET

attempts = 0,

status = ?,

queue = queue || ?,

is_dlq = TRUE, -- Set DLQ flag

process_after = ?,

processing_started_at = NULL,

failure_reason = ?,

updated_at = ?,

expires_after = ?

WHERE status != ? AND is_dlq = FALSE AND expires_after < ?;`

res, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

common.ReadyStatus, // status = ?

common.DlqSuffix, // queue = queue || ?

nowMs, // process_after = ?

common.MessageExpiredFailureReason, // failure_reason = ?

nowMs, // updated_at = ?

nowMs+fr.appConfigs.DlqTtlMs, // expires_after = ?

common.ProcessingStatus, // WHERE status != ?

nowMs, // AND expires_after < ?

)Query updates all expired messages in the standard queues that are not in the processing state (i.e., ready or failed),

and moves them to the corresponding DLQs by appending -dlq suffix to the queue name.

Attempts counter is reset to 0.

A new expires_after timestamp is set based on the DLQ TTL configuration. The default is 7 days, but you can override it via FORQ_DLQ_TTL_HOURS environment variable.

We are filtering out messages in the processing state, as they might be being processed by the consumers, and we don’t want to interfere with that.

This query uses the idx_expired covering index, so it is very fast.

Based on this job logic, you can see that it is possible that the expired message isn’t moved to the DLQ in the realtime, so it’s possible that the consumer fetches the expired message before this job runs. I believe it’s a reasonable compromise for the use case Forq is targeting.

ExpiredDlqMessagesCleanupJob

This job takes care of permanently deleting expired messages from the DLQs. It runs every 62 minutes.

This flow is quite simple, as we just need to delete the messages that are expired and are not in the processing state.

query := `

DELETE FROM messages

WHERE status != ? AND is_dlq = TRUE AND expires_after < ?;`

res, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

common.ProcessingStatus, // WHERE status != ?

nowMs, // expires_after < ?

)We are filtering out messages in the processing state, as they might be being processed by the consumers, and we don’t want to interfere with that.

This query uses the idx_expired covering index as well, so it is very fast.

FailedMessagesCleanupJob

This job takes care of moving failed messages from the standard queues to the DLQs. It runs every 6 minutes.

Here is the code snippet for the DB query:

query := `

UPDATE messages

SET

attempts = 0,

status = ?,

queue = queue || ?,

is_dlq = TRUE, -- Set DLQ flag

process_after = ?,

processing_started_at = NULL,

failure_reason = ?,

updated_at = ?,

expires_after = ?

WHERE status = ? AND is_dlq = FALSE;`

res, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

common.ReadyStatus, // status = ?

common.DlqSuffix, // queue = queue || ?

nowMs, // process_after = ?

common.MaxAttemptsReachedFailureReason, // failure_reason = ?

nowMs, // updated_at = ?

nowMs+fr.appConfigs.DlqTtlMs, // expires_after = ?

common.FailedStatus, // WHERE status = ?

)It updates all failed messages in the standard queues, and moves them to the corresponding DLQs by appending -dlq suffix to the queue name.

Attempts counter is reset to 0.

This query uses the idx_expired covering index, so it is very fast. Btw, it’s not a typo, SQLite can use the same index for different queries, which is pretty cool.

FailedDlqMessagesCleanupJob

This job takes care of permanently deleting failed messages from the DLQs. It runs every 89 minutes.

Here is the code snippet for the DB query:

query := `

DELETE FROM messages

WHERE status = ? AND is_dlq = TRUE;`

res, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

common.FailedStatus, // WHERE status = ?

)We are deleting all failed messages in the DLQs, as they are not going to be processed anymore.

This query uses the idx_status covering index, so it is very fast.

StaleMessagesCleanupJob

We have already covered this job above, so I won’t repeat myself here. Let’s proceed to the maintenance jobs.

Maintenance jobs

Currently, only the DbOptimizationJob job exists.

I considered adding the vacuum job as well, but since I know nothing about your workload, system, etc., I decided to leave it out of the box for now.

Without the context, it might do more harm than good, so I prefer to keep things simple and safe by default.

DbOptimizationJob

SQLite docs recommend running PRAGMA optimize; periodically to optimize the DB.

Here is the advice for the long-running connections:

Applications that use long-lived database connections should run “PRAGMA optimize=0x10002;” when the connection is first opened, and then also run “PRAGMA optimize;” periodically, perhaps once per day or once per hour.

I decided to go with the hourly interval, as due to the nature of MQs, there are a lot of inserts and deletes happening all the time, so the DB might get fragmented over time, and running the optimization periodically should help with that.

SQLite states that

This pragma is usually a no-op or nearly so and is very fast. On the occasions where it does need to run ANALYZE on one or more tables, it sets a temporary analysis limit, valid for the duration of this pragma only, that prevents the ANALYZE invocations from running for too long

So, this one is safe to run periodically, and might help with the performance of the queries without the noticeable overhead.

Here is the code snippet for the DB query:

_, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, "PRAGMA optimize;")No error handling needed, as if it fails, it fails. No big deal, as the job will run again in an hour.

Metrics jobs

Currently, only the QueuesDepthMetricsJob job exists.

QueuesDepthMetricsJob

QueuesDepthMetricsJob runs only if you have enabled the Prometheus metrics via FORQ_METRICS_ENABLED environment variable.

As the name suggests, it collects the depth of each queue (i.e., number of messages in the ready state) and exposes it via Prometheus metrics.

I covered the metrics in the Metrics Guide already, so I won’t repeat myself here.

This job runs every 30 seconds, as the queue depth is a critical metric for MQs, and having it updated frequently is beneficial. Also, it’s a purely read operation, so it doesn’t interfere with the write operations.

Here is the code snippet for the DB query:

query := `

SELECT queue, COUNT(*) as messages_count, is_dlq

FROM messages

GROUP BY queue, is_dlq

ORDER BY queue ASC;`

rows, err := fr.dbRead.QueryContext(ctx, query)As you can see, it’s a simple SELECT query that groups the messages by queue name and DLQ flag, and counts the number of messages in each group.

If you run EXPLAIN QUERY PLAN on this query, you’ll see this:

SCAN messages USING COVERING INDEX idx_for_queue_depth

USE TEMP B-TREE FOR ORDER BYIt’s an interesting combination of using the covering index and a temporary B-tree for ordering.

Generally, if I see USE TEMP B-TREE FOR ORDER BY, it’s a sign that there is a room for improvement, as SQLite needs to create a temporary B-tree to sort the results.

However, in this case, it orders the already grouped result, which is a small set of rows.

At this point, I believe that creating a separate index for this query is an overkill, as it would add unnecessary overhead to the write operations.

Let me know if metrics are too slow for you, and I might look into it again.

Alright, this covers the background jobs section. Let me briefly mention the Admin UI before wrapping up.

Admin UI

Additionally to the API and background jobs, Forq comes with a simple Admin UI that allows you to:

- view the list of queues and their depth

- view the messages in a specific queue (standard or DLQ)

- delete messages from a specific queue (DLQ-only)

- requeue messages from a specific DLQ to the standard queue (either one or all the messages)

More high-level details are available in the Admin UI Guide.

Since we are in the internals guide, let me share a few implementation details that might be interesting.

Admin UI runs on a different port (default is 8081) than the API (default is 8080).

Admin UI uses HTMX and DaisyUI over Go templates to keep things simple and lightweight. If you are not familiar with HTMX, you are missing out. It’s a great library that allows you to create dynamic web pages without writing any JavaScript by extending HTML with custom attributes. See some HTMX examples in the HTMX docs.

Hypermedia / HATEOAS API

If you are using HTMX, the REST API flow that returns JSONs is not the standard way of doing things. Hypermedia/HATEOAS is a way to go. If you joined the industry recently, you might not be familiar with these terms, as it’s not that popular nowadays. What it means in our case, is that the API returns HTML snippets instead of JSONs, and the client (i.e., Admin UI) just swaps the relevant parts of the page with the received HTML snippets.

If you want to learn more about HATEOAS & Hypermedia, here is a free online book from the HTMX creator.

I’m sharing this here, so you are not surprised when you see HTML snippets in the API responses, or in the Go code while inspecting the Admin UI implementation.

Here is the code snippet from the UI router that shows all the existing Hypermedia endpoints:

router.Use(csrfPrevention(ur.csrfErrorHandler, ur.env))

// unprotected login routes:

router.Get("/login", ur.loginPage)

router.Post("/login", ur.processLogin)

// protected routes:

router.With(sessionAuth(ur.sessionsService)).

Get("/", ur.dashboardPage)

router.With(sessionAuth(ur.sessionsService)).Post("/logout", ur.processLogout)

router.Route("/queue/{queue}", func(r chi.Router) {

r.Use(sessionAuth(ur.sessionsService)) // session auth for all queue routes

r.Get("/", ur.queueDetailsPage)

r.Get("/messages", ur.queueMessages)

r.Get("/messages/{messageId}/details", ur.messageDetails)

r.Delete("/messages", ur.deleteAllMessages)

r.Post("/messages/requeue", ur.requeueAllMessages)

r.Delete("/messages/{messageId}", ur.deleteMessage)

r.Post("/messages/requeue/{messageId}", ur.requeueMessage)

})Among endpoints, you can see that there are 2 middlewares applied to the protected routes:

csrfPrevention- protects against CSRF attacks by validating the CSRF token in the requestsessionAuth- protects against unauthorized access by checking the session cookie in the request

There is nothing you should do for CSRF, as Forq handles it automatically. Check the OWASP CSRF Guide if you want to learn more about this attack.

As for the session authentication, Admin UI requires you to log in with the same auth secret you use for the API, that is FORQ_AUTH_SECRET environment variable.

Once logged-in, Forq creates a secure (if not running in the local env) cookie named ForqSession in the LAX mode, that will leave for 7 days.

Forq keeps sessions in memory, so if you restart the server, you’ll need to log in again. No big deal for the Admin UI, as it’s not a critical service.

I will not go into much details about each and every endpoint, as I generally believe that Admin UI is not as critical part of Forq as the API and background jobs. Most of them are backed by SQL queries, and I have to admit that some of the select ones are not the most efficient. It explained by my decision not to add extra indexes just for the Admin UI, as it would add unnecessary overhead to the consumers and producers operations. Not worth it, imho.

However, let’s take a closer look at two admin operations that are quite important from the DLQ management perspective: deleting messages and requeuing messages.

Deleting a single message

Here is the code snippet for the DB query that deletes a single message:

query := `

DELETE FROM messages

WHERE id = ? AND queue = ? AND is_dlq = TRUE;;`

result, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

messageId, // WHERE id = ?

queueName, // AND queue = ?

)As you can see, it’s a simple DELETE query that uses the primary key lookup for the id, so it’s extremely fast.

The queue = ? part is just an additional safety check to ensure that the message is being deleted from the correct DLQ.

The is_dlq = TRUE part ensures that only messages from the DLQs can be deleted.

Forq doesn’t filter out the messages in the processing state, as this query is triggered by the admin user, who is expected to know what they are doing.

Deleting all messages in the DLQ

Here is the code snippet for the DB query that deletes all the messages in the particular DLQ:

query := `

DELETE FROM messages

WHERE queue = ?;`

res, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

queueName, // WHERE queue = ?

)As you can see, it’s a simple DELETE query that deletes all messages from the specified queue.

This is a potentially dangerous operation, so Forq assumes that the admin user knows what they are doing.

The UI will prompt the Are you sure you want to permanently delete all messages? This cannot be undone. confirmation dialog before proceeding with the deletion.

The query uses the idx_for_requeueing covering index, so it’s very fast.

Requeuing a single message

Here is the code snippet for the DB query that requeues a single message from the DLQ to the standard queue:

nowMs := time.Now().UnixMilli()

destinationQueueName := strings.TrimSuffix(queueName, common.DlqSuffix)

query := `

UPDATE messages

SET

queue = ?, -- Move back to regular queue

is_dlq = FALSE, -- Unset DLQ flag

status = ?,

attempts = 0,

process_after = ?,

processing_started_at = NULL,

failure_reason = NULL,

updated_at = ?,

expires_after = ?

WHERE id = ? AND queue = ? AND status != ?;`

result, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

destinationQueueName, // queue = ? -- Move back to regular queue

common.ReadyStatus, // status = ?

nowMs, // process_after = ?

nowMs, // updated_at = ?

nowMs+fr.appConfigs.QueueTtlMs, // expires_after = ?

messageId, // WHERE id = ?

queueName, // AND queue = ?

common.ProcessingStatus, // AND status != ?

)As you can see, it’s a simple UPDATE query that moves the message back to the standard queue by removing the -dlq suffix from the queue name,

and resetting the relevant fields to make the message ready for processing again.

The query uses the primary key lookup for the id, so it’s extremely fast.

Requeuing all messages in the DLQ

Here is the code snippet for the DB query that requeues all messages from the particular DLQ to the standard queue:

nowMs := time.Now().UnixMilli()

destinationQueueName := strings.TrimSuffix(queueName, common.DlqSuffix)

query := `

UPDATE messages

SET

queue = ?, -- Move back to regular queue

is_dlq = FALSE, -- Unset DLQ flag

status = ?,

attempts = 0,

process_after = ?,

processing_started_at = NULL,

failure_reason = NULL,

updated_at = ?,

expires_after = ?

WHERE queue = ? AND status != ?;`

res, err := fr.dbWrite.ExecContext(ctx, query,

destinationQueueName, // queue = ? -- Move back to regular queue

common.ReadyStatus, // status = ?

nowMs, // process_after = ?

nowMs, // updated_at = ?

nowMs+fr.appConfigs.QueueTtlMs, // expires_after = ?

queueName, // WHERE queue = ?

common.ProcessingStatus, // AND status != ?

)The same logic as for requeuing a single message, but for all messages in the DLQ, so no id filter here.

The query uses covering index idx_for_requeueing, so it’s very fast.

Be aware that requeuing a large amount of messages will create a load on consumers,

as the chances are that these messages will be the first ones to be picked up for processing if they are oldest in the queue.

Requeueing doesn’t reset the received_at timestamp, so the original order of messages is preserved.

Instead of conclusion

That was a long read, and it took me a few days to write it. If you got this far, you are a true Forq expert now, and can recreate it from scratch. Congrats!

Have fun using Forq!