Specification

This guide provides an overview of Forq’s features and design. This is a mandatory read to understand the capabilities and limits of Forq!

General Overview

Forq is a message queue service. As other MQs, it allows you to send messages to the queues, and consume them from the queues. So, unlike the request-response pattern, where the client sends a request and waits for the response, in the message queue pattern, the client sends a message to the queue and continues its work. The consumer will process the message later.

Forq is backed by SQLite, which means that the messages are persisted to disk, and will survive a server restart.

High-level Architecture

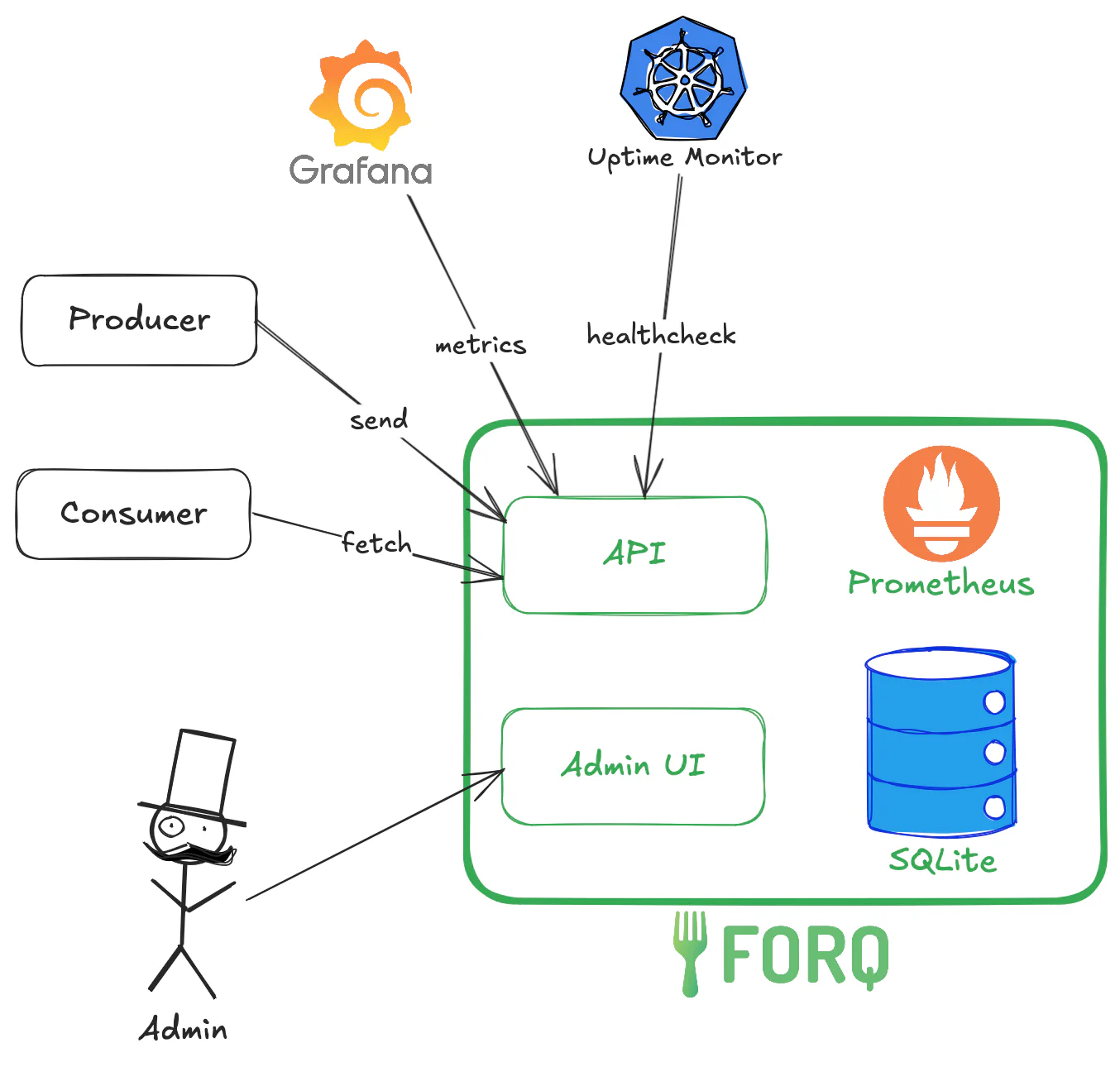

The green boxes represent the Forq service, which consists of:

- The API server, which exposes a REST API for sending and receiving messages, healtchecks, and metrics (if enabled).

- The Admin UI, which is a web interface for managing the queues and messages.

- The SQLite database, which stores the messages and queue metadata.

- (Optional) Prometheus metrics if enabled.

All of this is a single binary (or a Docker container) that you can run on your server.

The dark boxes and arrows represent the external clients that interact with Forq:

- Producers, which send messages to the queues via the API.

- Consumers, which receive messages from the queues via the API.

- Administrators, which manage the queues and messages via the Admin UI.

- Uptime monitoring service (like Uptime Kuma or Kubernetes), which pings the healthcheck endpoint to ensure that Forq is up and running.

- (Optional) Metrics server (like Grafana), which scrapes the metrics from Forq if enabled.

Message Queue characteristics

- At-least-once delivery: Forq guarantees that each message will be delivered at least once. However, in some cases, a message may be delivered more than once (e.g., if a consumer fails to acknowledge the message within the processing timeout).

- FIFO (First In, First Out): Messages are processed in the order they are received. This is done with the best effort, as if messages received with the difference of a few milliseconds, the order may not be preserved.

- Multiple producers and consumers: Forq supports multiple producers and consumers for each queue.

- Message Acknowledgement: Consumers must acknowledge or unacknowledge each message they receive. If a message is not acknowledged within the processing timeout, it is considered unacknowledged and will be re-queued or moved to the DLQ if it has exhausted its retries.

- Delayed Messages: Forq supports delayed messages, which are messages that are not available for processing until a specified delay period has passed.

Queues

There are 2 types of queues in Forq:

Standard Queues

These are the main queues where you send and receive messages. They support multiple producers and consumers.

By default, standard queues have a TTL (time-to-live) of 24 hours,

which means that messages that are not processed within 24 hours will be moved to the Dead Letter Queue (DLQ).

You can change the TTL by setting the FORQ_QUEUE_TTL_HOURS environment variable.

Dead Letter Queues (DLQ)

These are special queues where messages that could not be processed successfully are sent.

Each standard queue has its own DLQ. The DLQ name is the standard queue name with the suffix -dlq.

There are two ways how to process messages in the DLQ:

- via the Admin UI, where you can view, requeue and delete messages in the DLQ. Learn more in the Admin UI guide.

- via the API, where you can receive and delete messages in the DLQ. Basically, as with standard queues, just use the DLQ name.

By default, DLQs have a TTL of 168 hours (7 days), which means that messages that are not processed within 7 days will be deleted.

You can change the TTL by setting the FORQ_DLQ_TTL_HOURS environment variable.

If you are interested to learn more about internal implementation of queues, check out the Internals Guide.

Messages

Messages in Forq are strings, with a maximum size of 256 KB. Forq is chill about the message content, so you can send any string you want, including JSON, XML, or plain text.

Message Lifecycle

A message in Forq goes through the following states:

- Ready: The message is in the queue and is available to be received by a consumer.

- Processing: The message has been received by a consumer, but has not yet been acknowledged. The message is hidden from other consumers.

- Acknowledged: This is a virtual state, as once acknowledged, the message is deleted from the queue.

- Unacknowledged: Another virtual state that means that the message was explicitly unacknowledged (via the Nack endpoint). The message is moved back to the Ready state if there are still retries left, otherwise it is marked as Failed.

- Stale: Yet another virtual state that means that the message has been received by a consumer, but has not been acknowledged within the processing timeout. The message is moved back to the Ready state if there are still retries left, otherwise it is marked as Failed.

- Failed: The message has exhausted all its retries. For the standard queues, the message is moved to the DLQ. For the DLQs, the message is permanently deleted.

- Expired: Yet another virtual state that means that the message has exceeded its TTL. For the standard queues, the message is moved to the DLQ. For the DLQs, the message is permanently deleted.

“Virtual state” means that if you look at the DB, there won’t be such a state there. For DB, the message is either Ready, Processing, or Failed. The other states are just a way to describe the message lifecycle.

Things that you should know (and do)

No built-in rate limiting

Forq uses HTTP protocol for its API, which means that you can use any HTTP client to interact with it. Which makes it exposable to the attacks, like DDoS.

Forq doesn’t have any built-in rate limiting, so that’s on you. If you are running Forq in production, make sure to put it behind a reverse proxy (like Nginx or Traefik), Load Balancer or Cloudflare, and enable rate limiting there.

No built-in backup and restore

Forq uses SQLite as its DB, which is a file-based DB. When you run the Forq server, the logs will tell you where the DB files are located (it depends on the OS). It’s your task to back those files.

It’s not the best idea to simply copy those files. Instead, SQLite has a built-in backup API that you can use to create a consistent backup of the DB. You can find more information about it in the SQLite documentation.

It’s basically smth like this (if you are in the same directory where forq.db is located):

now = date +"%Y%m%d%H%M%S"

sqlite3 forq.db ".backup 'forq_backup_$now.db'"Use the backup API together with a cron job to create regular backups of the DB. Built-in Linux cron is good enough for that. It’s a good idea to back up files to a remote location, like Cloudflare R2, AWS S3, Google Cloud Storage, or any other place outside the server where Forq is running.

If that sounds too complicated, ask AI to assist, it’s just a few lines of Bash script.